College hockey has a long history and a dedicated fan base, but it is a little brother in the family of college sports.

In terms of participation, revenue, and interest, men’s hockey often trails sports like football and men’s basketball, and by a wide margin. As a result, athletic directors and university presidents have occasionally made decisions that irked their hockey programs and their fan bases, even if those decisions might have benefited a school or athletic department as a whole.

One glaring example is the recent case of conference realignment in college hockey, which upended the competitive balance among conferences nationwide.

Or did it?

At the root of the recent conference-realignment drama in college hockey is the fact that so few schools play hockey at all. As a review for the uninitiated reader, Division I men’s hockey has 60 schools, compared to about 250 schools in Division I college football.

Because of these low numbers, each typical athletic conference rarely includes enough hockey programs to make a full hockey conference, so those programs have to look elsewhere to fill their schedules. Minnesota and Wisconsin, for example, play each other in the Big Ten Conference in most sports, but played hockey for years in the WCHA with schools like Minnesota Duluth and St. Cloud State, who play other sports at the Division II level.

To be sure, the WCHA was one of the elite conferences in college hockey, and also included stalwarts like North Dakota and Denver. However, that Denver and Minnesota were in the same conference at all was a byproduct of the scarcity of college-hockey programs nationwide.

This mismatch of different-sized schools may have made for good hockey and intense rivalries, but it made for bad business. Specifically, as the revenue for football and men’s basketball started to increase, and as the biggest traditional conferences started to create their own television networks as a means to collect that revenue, hockey got caught in the middle. Consequently, the landscape of college hockey shifted when two storied conferences were ripped apart five years ago.

Conference realignment is a complex process, to be sure, but in the case of college hockey, the story is easy to (over)simplify. As mentioned, the Big Ten was not a hockey conference, in no small part because it had only five schools with hockey programs. However, after Penn State recently founded its hockey program, the Big Ten found itself with six hockey schools, the minimum number to make a full-fledged hockey conference in the eyes of the NCAA. Talk of a new Big Ten hockey conference was immediate. If and when the other Big Ten schools protested leaving their established hockey conferences, they were reminded of the revenue from having other sports on the Big Ten’s television network, and were strongly encouraged to join Big Ten hockey.

Unsurprisingly, the Big Ten announced its new hockey conference for the 2013-14 season, pulling its members from the two major hockey conferences in the Midwest and West: the WCHA and the CCHA.

A drastic chain of events ensued. Most of the other powerhouse programs from the WCHA seized the opportunity and formed the nucleus of a new hand-picked conference, the NCHC. The old CCHA disbanded, and many of the remaining schools from the original two conferences regrouped to restructure the WCHA. After the dust settled, there were three conferences where there had been two, with two new conferences (the Big Ten and NCHC) and one longtime conference that had lost its most successful programs (the WCHA).

The consensus among many fans and sportswriters was that the NCHC was the new dominant hockey conference in the Midwest and West, if not the country, while the Big Ten was a poorly arranged marriage of football schools. But then something surprising happened: just this year, the fifth year of the new conference structure, three Big Ten teams made it to the Frozen Four. It was not just a fluke, either, as two of those teams, Ohio State and Notre Dame (which had joined the Big Ten just that year), were ranked in the top five for much of the season. Of course, Duluth from the NCHC ended up winning the championship in St. Paul, but the question remained: was the Big Ten better than most people thought?

This article analyzes the national success, both recent and all-time, of the major conferences in college hockey. Specifically, it documents the distribution among current conferences of national championships, appearances in the Frozen Four, and top seeds in the national tournament.

For comparison, it also documents the same distributions among previous conferences, before the recent realignment. In short, it addresses which conference is best, as well as which conference has been best, according to both the current and previous conference structures.

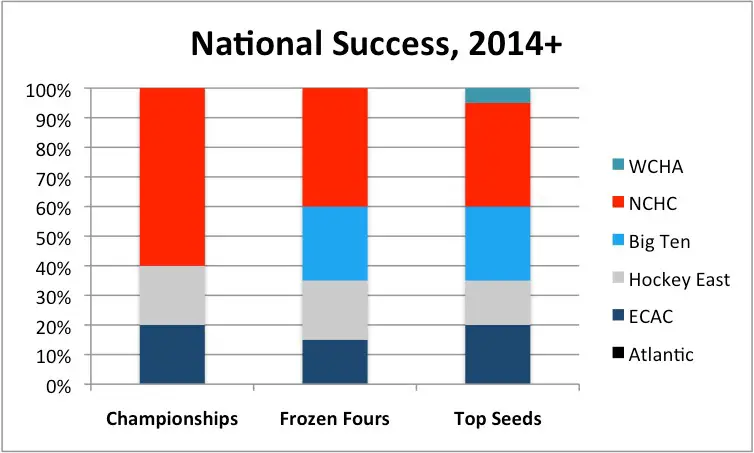

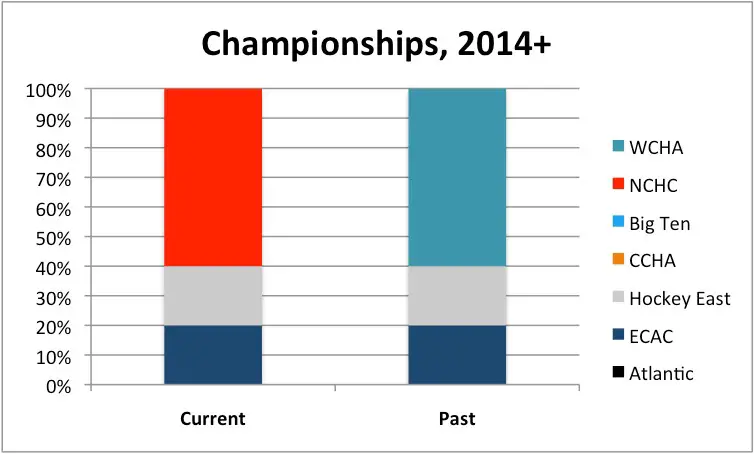

First, how have the new conferences fared since realignment? Since the creation of the Big Ten and NCHC five years ago, two champions have come from eastern conferences (Union of the ECAC and Providence of Hockey East), and three have come from the NCHC (North Dakota, Denver, and Duluth) (Figure 1). The NCHC has also led the nation in number of Frozen Four teams, as well as top seeds in the national tournament (Figure 1). Overall, the NCHC has led each of these three major categories since its inception, providing over half of the national champions, almost half of the Frozen Four teams, and a third of the top regional seeds.

Figure 1:

What about before realignment? How do the programs in the NCHC stack up against other conferences in terms of historical success?

What about before realignment? How do the programs in the NCHC stack up against other conferences in terms of historical success?

First, a disclaimer. Statistics over long periods, like over the seventy-one years of the NCAA hockey tournament, can be misleading for several reasons. Chief among them is relevance due to memory: winning a hockey championship 70 years ago is less important to fans, as well as to players and recruits, than winning last year, or even seven years ago. Similarly, winning a championship of a nascent sport, as hockey was 70 years ago, is a much different feat than winning a championship from among a larger, more balanced field of teams.

For example, the original format of the national tournament included only four teams, just like today’s Frozen Four. Michigan appeared in the first 10 tournaments, winning the championship six times. Should each of these appearances and championships be weighed evenly against championships and Frozen Four appearances in today’s longer tournament with more teams? It’s a problem that dogs historians and statisticians in all sports.

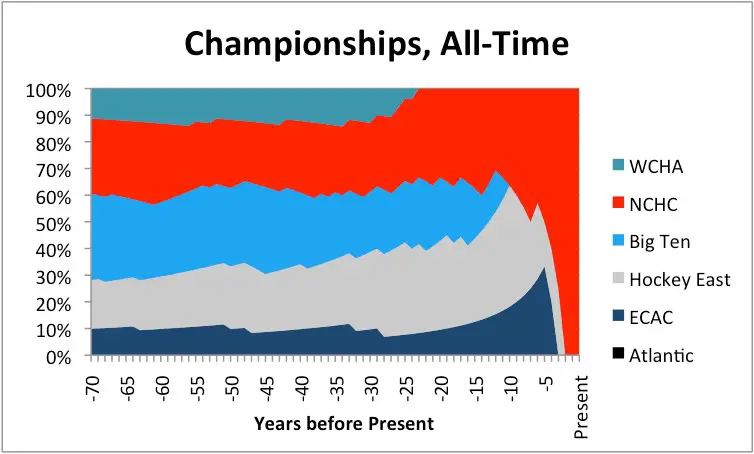

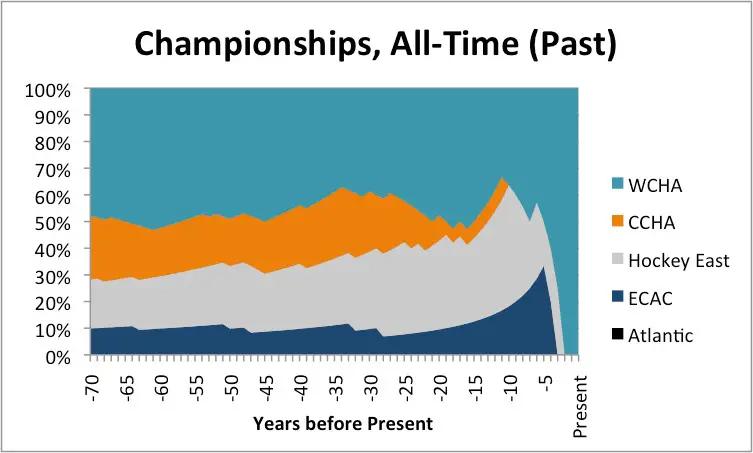

We will try to combat that problem using the kind of graph depicted in Figure 2. The graph represents the percentages of championships won over time, but does so relative to the present day.

Figure 2:

That is, the graph builds percentages backward from the present day, instead of beginning with the first tournament. This format intentionally over-represents recent history compared to distant history, just as fans do. As an example, consider that the NCHC has dominated championships in recent years, while the Big Ten has more championships over the history of the entire tournament.

That is, the graph builds percentages backward from the present day, instead of beginning with the first tournament. This format intentionally over-represents recent history compared to distant history, just as fans do. As an example, consider that the NCHC has dominated championships in recent years, while the Big Ten has more championships over the history of the entire tournament.

The right side of the graph, which is closer to the present day, shows the percentages of championships won in recent years, and is mostly red, representing the NCHC. The left edge of the graph, however, shows the ratio of all-time championships among conferences, and is about equal parts red and light blue, the color representing the Big Ten. Here, Michigan’s early dominance is fairly represented, but because the graph shows percentages of champions won over time dating from the present, Michigan’s string of early championships is dwarfed by the already large number of total championships in the denominator, and the graph is never predominantly light blue.

In sum, Figure 2 shows that the NCHC has dominated championships in recent years, but actually falls slightly behind the Big Ten all-time (20 vs. 23). Hockey East (13), the WCHA (eight), and the ECAC (seven) form a second tier behind the leaders.

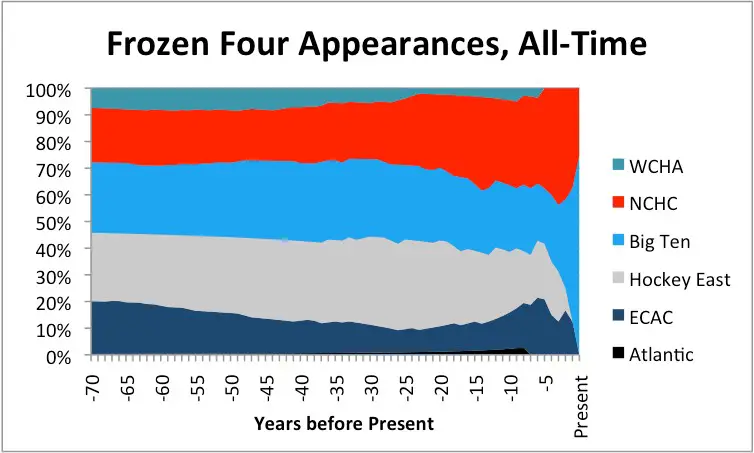

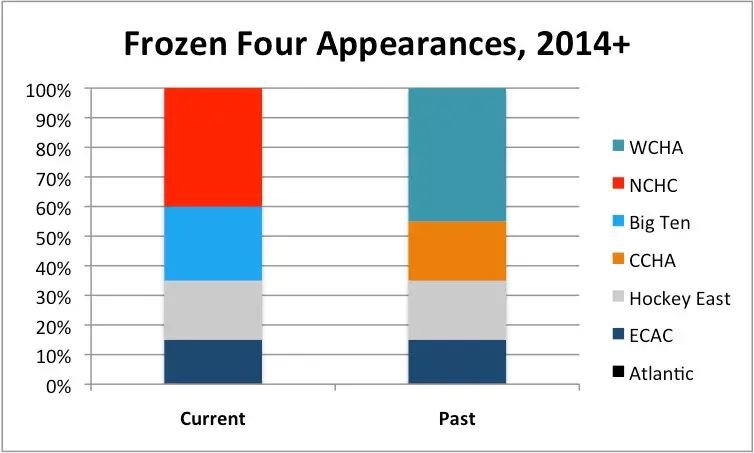

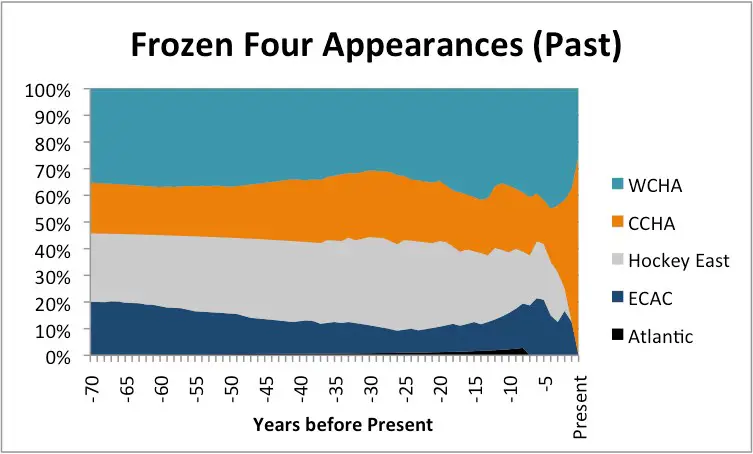

The same pattern emerges for appearances in the Frozen Four (or, as it was simply called for most of the tournament’s history, the national semifinals; Figure 3). On the right edge of this graph we see the Big Ten’s recent feat of three of the Frozen Four teams, but that dominance quickly dwindles to demonstrate the consistent success of NCHC programs over the past decade. Overall, Hockey East and the Big Ten have fielded the most teams in the national semifinals, with about half of the all-time participants between them. The NCHC and ECAC each have fielded about 20 percent of the semifinalist teams all-time, with most of the remaining 10 percent going to the current WCHA.

Figure 3:

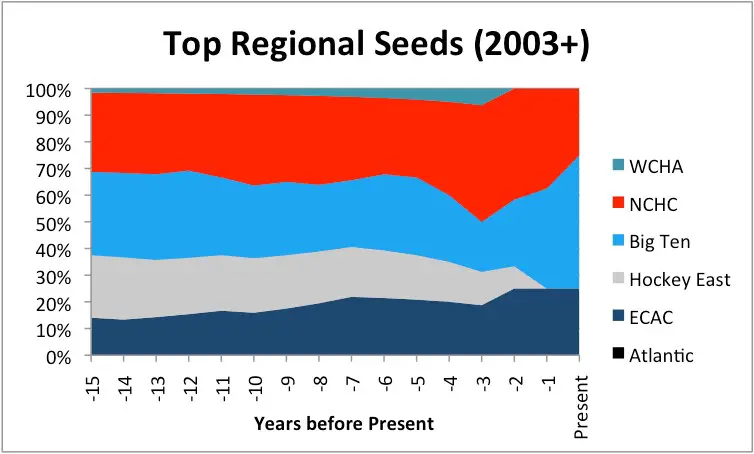

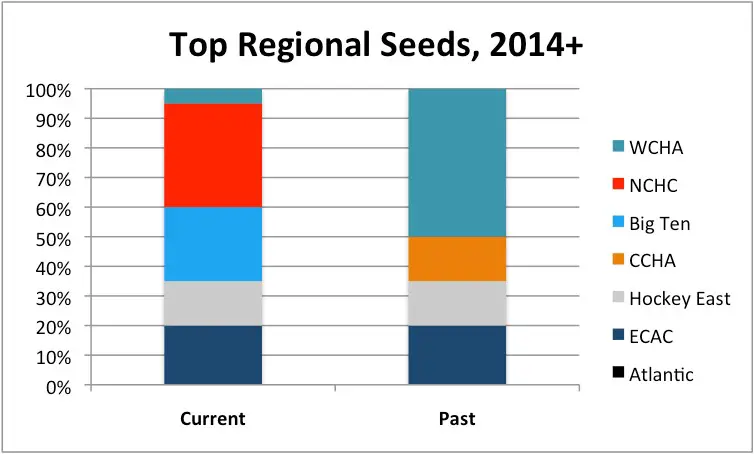

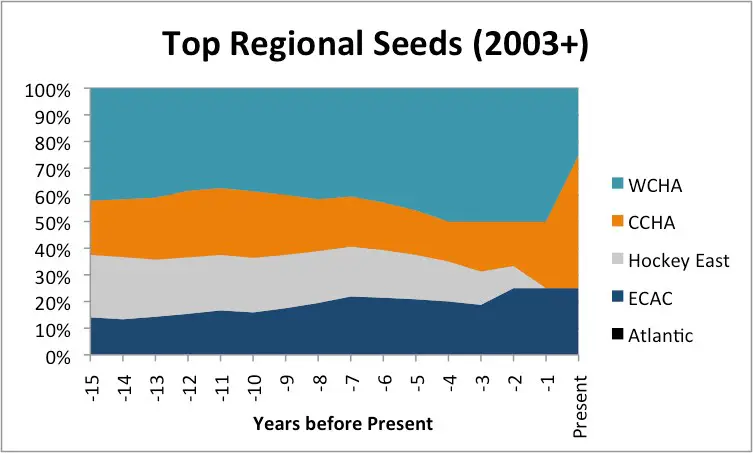

Again, the same pattern emerges for the top regional seeds since the adoption of the tournament’s current format in 2003 (Figure 4). Very recent history favors the NCHC and the Big Ten, but longer-term results show balance between the Big Ten (20), the NCHC (19), and Hockey East (15), with the ECAC (nine) and the WCHA (one) bringing up the rear.

Again, the same pattern emerges for the top regional seeds since the adoption of the tournament’s current format in 2003 (Figure 4). Very recent history favors the NCHC and the Big Ten, but longer-term results show balance between the Big Ten (20), the NCHC (19), and Hockey East (15), with the ECAC (nine) and the WCHA (one) bringing up the rear.

Figure 4:

Overall, the current conference alignment represents a wide distribution of all-time success, including national championships, appearances in the semifinals, and top seeds.

Overall, the current conference alignment represents a wide distribution of all-time success, including national championships, appearances in the semifinals, and top seeds.

All of this begs the question of how the distribution of success would look according to the previous conference alignment, before the creation of the Big Ten and NCHC. (For this we will use teams’ affiliations in the last year before realignment, the 2012-2013 season.)

Regarding championships in the past five years, the NCHC can merely be swapped for the WCHA, as its three champions (North Dakota, Denver, and Duluth) were all WCHA schools (Figure 5). Similar swapping could occur regarding Frozen Four appearances (Figure 6) and top regional seeds (Figure 7), where most of the Big Ten’s recent success has been due to teams that hailed from the CCHA, while the WCHA’s success increases only minimally after reclaiming Minnesota.

Figure 5:

Figure 6:

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

Figure 7:

Of course, one cannot put too much stock into simple counterfactuals like what would have happened if the old WCHA would have remained intact.

Of course, one cannot put too much stock into simple counterfactuals like what would have happened if the old WCHA would have remained intact.

As a case in point, during the 2018 tournament, Duluth emerged from a region that also included St. Cloud State, which is also in the NCHC, and Minnesota State, which is in the WCHA and has been since before realignment. If realignment had not happened, three schools from one conference probably would not have been assigned to the same four-team region.

Considerations like this one are in addition to more obvious and bigger problems with “what-if logic” (e.g. every team’s schedule would have been different in the old conference system, likely changing the outcomes of the regular season and conference tournaments, making the comparisons of the actual results and a hypothetical result nearly meaningless).

With that said, it is not unreasonable to conclude that, under the old system, many of the dominant teams in the national stage would have continued to hail from the old WCHA, for example. If nothing else, it is a fun thought experiment.

That thought experiment can help us make a larger point about all-time success, one that matches what many fans of the WCHA and NCHC have been saying for decades: the WCHA was a uniquely successful conference in college hockey.

Figures 8, 9, and 10 show how the WCHA was overrepresented in terms of all-time championships, appearances in the national semifinals, and top regional seeds in the national tournament. Altogether, these findings show that the current alignment of conferences in college hockey represents greater balance regarding historical success, at least compared to the previous alignment, which was dominated by the WCHA.

Figure 8:

Figure 9:

Figure 9:

Figure 10:

Figure 10:

The merit of competitive balance is a common argument across the sports world. Regarding the college hockey’s national tournament, because top seeds would be spread more evenly among conferences, more balance might equate to novel matchups between non-conference opponents deep into the tournament. This is in contrast to some of the twilight years of the WCHA, for example, when matchups in the Frozen Four in April strongly resembled matchups in the WCHA’s Final Five conference tournament in March.

The merit of competitive balance is a common argument across the sports world. Regarding the college hockey’s national tournament, because top seeds would be spread more evenly among conferences, more balance might equate to novel matchups between non-conference opponents deep into the tournament. This is in contrast to some of the twilight years of the WCHA, for example, when matchups in the Frozen Four in April strongly resembled matchups in the WCHA’s Final Five conference tournament in March.

Toward the latter point, though, having several dominant teams in the same conference might produce better hockey on the whole, as some fans might get to watch the same marquee matchup four or five times per season (e.g. two full home-and-away series during conference play and perhaps one game during the conference tournament).

Of course, such discussions might be moot as long as the balance of power remains with the WCHA/NCHC, where it has lingered in recent years.

However, as the pendulum inevitably swings elsewhere, the fight to claim supremacy among conferences in college hockey might be more evenly matched than many casual fans might think.

P. A. Jensen is a freelance sportswriter and editor of RuralityCheck.com. He lives in northern Minnesota with his wife and son.