If you could write the perfect story about a hockey broadcaster, it would probably center around someone on a journey of self-discovery.

It would have a main character who found a passion and calling within the game, a protagonist inspired by the game’s speed and intensity.

It would turn into a love at first sight and stumble through a requisite learning curve until, finally, a melding of broadcaster to game occurred.

It would incorporate other layers capable of inspiring readers and observers, and it would touch every supporting cast member. The personality development would tingle a range of emotions, and the voice would transcend the game while remaining a piece of the overall experience.

Trey Matthews knows how to write that story because he very organically made himself the protagonist. He didn’t grow up in hockey rinks, and he didn’t skate on frozen ponds.

Still, he developed a love for a foreign game by simply watching it and learning the culture of the world’s fastest sport at Adrian College, a Division III school with a number of club hockey programs.

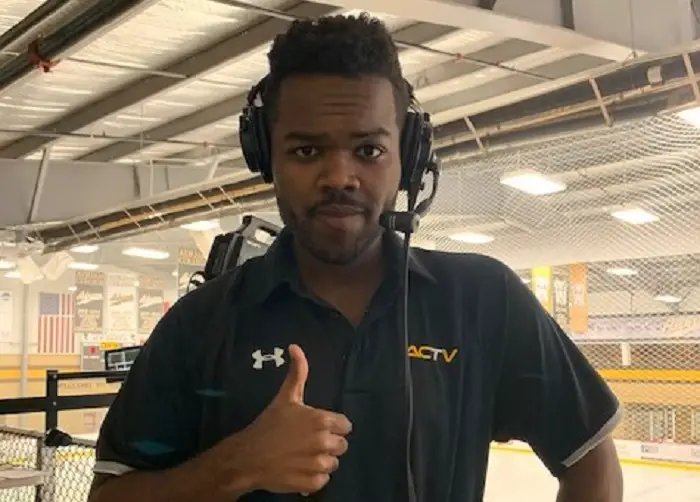

He’s now an entrenched part of the Bulldogs’ sports culture as the play-by-play voice of the ACHA Division I women’s club program.

More than that, he’s a trailblazer and an icon for the college hockey game as one of the only Black broadcasters in the hockey world. The link, a source of pride that hockey hopes can one day be the norm, connects him to the National Hockey League, where he developed a relationship with Everett Fitzhugh, the play-by-play voice of the expansion Seattle Kraken.

“Trey’s just so dedicated to his craft,” said Gabriel Schray, a multimedia specialist at Adrian College. “I can’t get over it with him. A lot of students talk about how badly they want to broadcast, but Trey has the dedication and grit. He doesn’t have a gimmick or a trick. He’s blessed with talent verbally, and he puts in time to watch the team. He goes to practice and takes notes. He thinks about what he wants to talk about and how he wants to say it. That’s something not a lot of professional announcers do. That tells me how there’s a future (in broadcasting) for him.”

It’s a monster accomplishment for a student-athlete who didn’t exactly have the traditional hockey background. He grew up in Detroit and moved to Philadelphia but didn’t latch onto either city’s culture within the sport. He was a baseball player, and he wanted to continue his career at the next level after a successful high school career as a player capable of playing anywhere on the diamond. Hockey was nowhere on his radar, even when he chose to enroll at Adrian.

“It meant a lot for someone like me because there wasn’t an easy path to play baseball at the next level,” Matthews said. “I needed to find ways to show that I belonged on a baseball field. In the country, we talk about back roads. I had to take the back roads to get from one place to another, so it meant a lot to me (to become involved with the team).”

Adrian College is one of those places where sports feeds student life. The Division III school is a member of the Michigan Intercollegiate Athletic Association but sponsors both men’s and women’s hockey within the NCHA as part of its larger, seven-strong number of hockey teams. There are three men’s club programs, one in each division of the ACHA, with a Division I and Division II club program available for women.

“(The sports) are one of the biggest draws to Adrian College,” club baseball head coach Brent Greenwood said. “It adds some things that people scratch their heads, and club baseball was (one of those sports) because there wasn’t a team or a league. We needed to hit the ground running as a program.

“Whoever I was reaching out to was just interested in playing. That led me to Trey. He’s a good student who wanted to play baseball. We wanted kids like him because he came to play baseball but found his calling doing something different – like broadcasting.”

That volume of programs foster a deep culture and appreciation among the Adrian College student base, but it further creates opportunities for students to get involved along the ancillary edges. One of those outlets is the school’s television station – ACTV – which houses a full production unit for students. Those interested in broadcasting sports are encouraged to apply, and Matthews threw his name into the pot of potential broadcasters after meeting with Schray, the station director.

“ACTV was something that was really cool for me as an undergraduate,” Schray said. “It’s different from how other schools run things because ACTV has always been student-focused. It’s student-controlled as much as possible. We had hired a whole new staff, and Trey was one of those guys (who applied). We talked about his interest, and he was super into it. He recorded himself pretending to call some sports, and he applied. I felt he really cared about it.”

“I would love to take credit for it, but my mom is the one that was urging me to get into broadcasting,” Matthews added. “She thought she saw a career in it, and she was urging me to add communications as a major. I was friends with one of the student directors from ACTV, and he recommended me to his boss. I was just a standard Adrian College student, though last year I did add communications as a major.”

Matthews’ first assignment was to cover hockey as a color commentary analyst, a role he embraced. He didn’t know much about the game but felt confident in his ability to analyze his perspectives. He didn’t need to study the flow of play or describe anything beyond the deep-rooted analysis, and it would ease him into a sport he hadn’t really watched.

That all changed, though, the day before the game. His broadcast partner bowed out of the role and thrust Matthews into the featured, play-by-play role. In his first-ever broadcast, Matthews called a game he didn’t know, with players he couldn’t recognize, with rules he didn’t understand, and with a lightning-fast, split-second speed and flow.

“The first time he called a game, (sports information director) Patrick Stewart called me and complained,” Schray recalled. “Trey was so green that he didn’t know what he was doing. So we sat down and went over terminology. It took about three games to figure it out. We watched the HBO Sports special from Mike Emrick calling the ECHL and Bowling Green and how he eventually made it to NBC Sports.”

“That broadcast was an absolute disaster,” Matthews emphasized. “It was so bad that we received complaints, and I was told not to go on the air until I had a conversation about what I did wrong. I just knew that I liked the game. It was so much fun and energetic. It’s unpredictable, and so much can happen in one game. (That first game) made me determined to do hockey because it was so much fun.”

Undeterred, Matthews met with Schray to cover specifics, and he realized quickly he needed to learn this new game. So he did what any college male would do in that situation – and played video games. He bought EA Sports’ NHL franchise video game and played it until he could recite rules and recognize the game play.

“You realize that he really puts everything he has into whatever he’s doing,” Greenwood said. “No matter what you tell him, he’s going to put everything into it. That’s led to his success because he just dove in, researched, and watched hockey.”

The gradual improvement eventually shattered Matthews’ own expectations, and he built the trust with Schray to begin calling games more and more frequently. What started as a freshman year experiment became a passion, and by last season, his sophomore year, he was named the official play-by-play broadcaster for the Bulldogs’ Division I women’s club team.

That’s when Matthews started to realize that he sort of stuck out in the game of hockey. He realized there weren’t that many African American players, but he saw even less Black broadcasters. He started looking around and confirmed what he thought until he found another name: Everett Fitzhugh, then the play-by-play broadcaster for the Cincinnati Cyclones of the ECHL.

“It crossed my mind after the season ended that I was an African-American in a predominantly white sport,” Matthews said. “I knew there was a shortage of play-by-play announcers of color. There are a lot of analysts like me, but there aren’t a whole lot of play-by-play announcers. It made me ask if there were any Black hockey announcers, and I found Everett Fitzhugh.

“My dad suggested for me to reach out and see what would happen if I shared my story,” he continued. “I hadn’t been in the industry for so long, but I felt I had a story to tell. That summer, I tweeted out my story about being a Black play-by-play announcer from Detroit. I tagged Everett in it, and he responded. We exchanged emails and phone numbers, and it opened a door for so many opportunities.”

Diversity in hockey has always been a complex, difficult conversation, but it came into focus during the ongoing racial reckoning in American society. In the NHL, it hit an initial zenith in early August when the Seattle Kraken, an expansion franchise set to start play in the 2021-22 season, named Fitzhugh as their team broadcaster.

A Detroit native himself, it’s the first time in NHL history that a franchise will feature a Black play-by-play announcer.

“To hear that other people are chasing their dreams to and trying to become hockey media members, writers, broadcasters – even fans – that is something so special,” Fitzhugh told USA Today Sports in August, “because I was that Black kid growing up in Detroit who didn’t have those influences.”

“Anyone who wants to look up to me, the same way I looked up to Everett, if we can do it, they can do it,” Matthews said. “I don’t want anyone to feel like they have to be in a box with a stereotype. Nobody can say someone should do something or like certain things. Like whatever you want and do whatever you want. Break down those walls. Don’t let someone trap you in a box saying that you can only do certain things. If you take a risk, and you enjoy it, go for it.”

The relationship between the two is a sign that hockey is finally starting to crack an uncomfortable glass ceiling. Matthews is achieving heights at Adrian College because he worked at broadcasting and is making himself a worthy on-air talent. He understands the competitive nature of the position and how selective broadcasting is as an industry.

He is appreciative of the moment, of his mentorship from Fitzhugh, and of his position as a potential groundbreaker in the game of hockey.

“That’s who Trey is,” Greenwood said. “He isn’t going to care about stereotypes or bad thoughts about him. He’s going to put his mind into something and grind out. He’s going to push forward, no matter what’s going on. He locked into hockey and went overboard. Now that he has the terminology, that he knows the game, that he’s still learning, he’s going to do an extraordinary amount.”

“I want kids to think that they can do it if I can,” Matthews said. “When I got the job at ACTV, I thought I would do basketball because that’s a sport that I knew. I took a risk and expanded my horizons after watching a game. I thought a game was fun, and it would fit my style of broadcasting. I’d rather call hockey (now) than a basketball game. Having called both, I made the right decision.”