The goals came fast near the end of the period, which ended 3-1 in favor of Oswego. CJ Thompson scored on the power play at 16:33, and Paul Ruta scored just 16 seconds later to put New England on the board. With 56 seconds to go in the period, Thompson got his second of the game, roofing the puck past Pilgrims netminder Matt Lyon.

And We’re Underway for Game Two

..and it’s 1-0 Oswego 2:12 in. Garren Reisweber on a wraparound.

A new face in the linup from NEC – Brian Pouliot, a transfer from New Hampshire. Pouliot played 52 games for the Wildcats his first two seasons but hadn’t played so far in his junior campaign.

Burning Down The House

That familiar ’80s Talking Heads anthem welcomed fans back into the Campus Center Ice Arena a few moments ago. About 50 minutes before game time, fire alarms went off, sending fans and players outside. Game time is now slated for about 7:30 p.m.

Update: a blown fuse in an exhaust fan in the concession stand was blamed for the alarm. The redolent smell of cheeseburgers is wafting through the barn.

Third Meeting?

A win tonight by Oswego would set up the third meeting this season between the Lakers and Elmira. The tournament hosts took the first two games, 2-1 at the Murray Athletic Center and 5-2 at home. A championship game between these two interstate rivals would be a barnburner — and despite Oswego’s two earlier wins, I wouldn’t count out what would be the first Laker loss at the hands of a seemingly rejuvenated Elmira squad.

Pivotal Win?

Last season, Elmira went on a second-half tear that propelled the Soaring Eagles to an NCAA berth and a goal away from the championship game. The team is off to a slow start again this year. Could the comeback in this game and a convincing win over St. Thomas be the spark that sets things right for Tim Ceglarski’s squad?

If they play like they did in the final 45 minutes, they just might. But it’s a tough hill to climb in the ECAC West, arguably the toughest top-to-bottom league in D-III.

And That’s Your Final

7-3 Elmira. All Soaring Eagles after the first 15 minutes or so. I’m going down to talk to the coaches and will post a recap shortly.

7-3 Midway Through the Third

St. Thomas got one back on a breakway by Kevin Rollwagon at 6:44, but a minute later, a giveaway in the Tommies’ zone results in a goal by Dave McKenna, who strips a defenseman of the puck and beats goaltender Treye Kettwick low glove. 7-3.

All Soaring Eagles

Two quick goals to open the third period, and it’s 6-2 Elmira. Stefan Schoen scored off a tip on a pass from Darcy Pettie to make it 5-2 57 seconds in, and at 1:37, Andrew Bedford made it 6-2.

Not Like The Old Days

It’s a little disappointing to see the small turnout of Elmira fans here for the early semifinal. Soaring Eagle fans used to be some of the best traveling faithful in D-III. There is a smattering of purple-clad Eagle enthusiasts here, but few than 100. In their heyday, you’d probably see 400 or 500 fans traveling up from the Southern Tier. The arrival of the UHL Jackals really depleted that Elmira fan base — even games at the Murray only draw a fraction of the 3,000-plus they used to draw.

Change of Momentum

Early in tonight’s contest, I wondered what had happened to the Elmira squad that had skated so well with Middlebury last spring. St. Thomas was blowing right past them up the ice and it was looking like a long night for the Soaring Eagles. That late power-play goal by Ryan Arnone seemed to stem the tide. Three unanswered here in the second seems to have ignited the crisp passing and quick transition game that characterized Elmira’s storybook playoff run.

Wow – Now 4-2 Elmira

Two more goals for the Soaring Eagles and it’s now 4-2. Derrick Ryan beat Maida glove side with a backhand at 4:22, and Russel Smith’s power play goal from the slot has made it 4-2 at 6:20.

Early in the Second – Tied at Two

Elmira looked awful in the opening minutes of this one, but has rallied back from an early 2-0 deficit.

St. Thomas opened the scoring at 2:20 when Ryan Hoehn got his second of the season off a feed from Alex Coles. Just 1:22 later, Hoehn struck again, blowing down the left wing shorthanded, and beating Soaring Eagle goaltender Casey Tuttle five-hole. St. Thomas had several more scoring chances after that, and was using their speed well.

Elmira got a power play goal with 1:01 to play in the first. Some nice passing found Ryan Arnone all alone at the back door, and the put it in the weak side to cut the Tommies’ lead in half.

Elmira got the momentum going its way with the tying goal just 38 seconds into the second period. Justin Joy’s shot glanced off a defenseman’s skate and past St. Thomas goaltender Jake Maida.

Oswego’s Campus Center Ice Arena – First Impressions

I’m in the pressbox at the new Campus Center Ice Arena on the campus of Oswego. I’ll get to the action between Elmira and St. Thomas in the opening game of the Pathfinder Bank Oswego Classic in a few minutes, but for now, I’m taking in this gorgeous facility:

1. It’s big, bright and open. If you’ve been to Cheel Arena at Clarkson, this building is on par with that one.

2. The acoustics are great.

3. The pressbox has great vantage points. I’m sitting on the redline about 50 feet up.

4. Not much atmosphere, but it’s the early game and the Lakers aren’t playing yet. Even so, school is out so I don’t expect a sellout tonight – officials here are hoping for 1,500 in an arena that seats 2,513. That’s one area where the old Romney Fieldhouse is going to be tough to replace – it could get electric in there.

5. I’m not a big Steve Levy fan, but he did donate what is apparently a large sum (matched by his employer, ESPN) for the pressbox. The six figure donation apparently called for Levy’s name to be splashed in foot-high letters across the back wall of the box. So props to Steve for the donation…but dude, low key would have been the way to go. I guess he wanted to make sure everybody in Oswego County could read it.

Back later with more on the game(s).

Northeastern Captain Mike Morris Has Appendectomy

Northeastern Senior captain Mike Morris has undergone an appendectomy. It has been called “not serious” and the “surgery went fine” according to Northeastern University.

The timetable for Morris’ return is not clear yet. He may be able to play as early as the Jan. 5 game versus Boston College but will have to be cleared by doctors first.

On the season Mike Morris has six goals and seven assists and is tied for first on the team in points.

Midnight Sun

Union head coach Nate Leaman was sitting in his hotel room in Mora, Sweden. Currently an assistant with Team USA at the World Junior Championship, Leaman has done a ton of work for both his program at home, getting it ready to compete this season, and for USA Hockey by assisting head coach Ron Rolston to select and shape this year’s entry at the WJCs.

That puts stress on Leaman because of the battles he fights for Union on the recruiting front, as well as in competition with a consistently improving conference. However, the experience of representing his country coupled with such a grandiose team-building experience only bode well for him and his program.

“It confirms what I have always believed, and that is work ethic and execution win games,” said Leaman, who has seen Team USA give two strong efforts despite two losses. “What has hurt is our lack of finish.”

The Americans were trapped to no end against Germany and lost in OT. Then they were beaten by a Canadian squad which feels that anything less than a gold medal (Canada is the two-time defending champion at this tourney) is a total failure. Canada remembers a gold medal-game loss to Mike Eaves’ crew in Finland in ’03.

“We really finished well in our pre-tourney exhibitions and we have struggled in our first two games,” said Leaman. “We hit four posts against Germany, and then missed an empty net. If you hit four posts in one tourney you are unlucky. But to hit four in one game?”

What has eluded the Americans, and what they are striving for in their Saturday game against Slovakia, is the first goal. On a team loaded with talent, scoring was not seen as a problem, but as Leaman pointed out, the two goalies they have faced are one-two in goals against average in the tourney, and hot goaltending wins short tourneys. The heroics of Al Montoya three tourneys ago are still fresh in Canada’s memory, as Montoya helped the Americans K.O. the Canadians to win gold.

The squad, led by a ton of WCHA’ers in Kyle Okposo, Mike Carman and No. 1 overall pick (’06 draft) Erik Johnson of Minnesota. That core is well supported by Badgers Blake Geoffrion and Jack Skille, Michigan State phenom Justin Abdelkader, and Jimmy Fraser of Harvard.

“No one really realizes behind the scenes what a great leader Fraser is,” said Leaman, who was an assistant at Harvard prior to Fraser’s arrival in Cambridge. “Kyle Lawson (Notre Dame) is also an outstanding leader.”

Leaman points to one of Team USA’s three major junior players as someone fans should be keeping an eye on. Buffalo, N.Y., native Patrick Kane, who skates for the OHL’s London Knights, is draft-eligible in 2007 and has scouts excited about his NHL potential. Kane, with his ’88 birth year, is considered by Leaman to be the team’s best pure talent.

“However, what really impresses me is that tourney-wide, every player is really good,” Leaman said after watching the Slovaks play Thursday. “The Slovaks have a really good third line. Two of them executed a great two-on-one tonight. These Europeans are very talented. All have great stick skills and they can all shoot, lines one through four are very balanced.”

For Team USA, the talent must shine in game three. The team does not lack players who have been on the international stage, as most of them have been through the U.S. NDTP program or were on last year’s team.

“We have a lot of experience on our roster, guys who know what to expect in international play,” said Leaman. “Right now I am pretty positive. There is a lot left to play. However, one bad game really costs you. In college you can outshoot someone 39-16 and lose, but not at the World Juniors. We need to get on the board early; that will really help with our confidence.”

An interesting side note to all of this is the USA-Canada matchup, with Canada’s team of mostly major junior kids versus the U.S. team of mostly NCAA players. The rivalry for players between these two great development systems, and what is considered “the best route” to the NHL, has existed for the past 26 years since the USA won gold at the Lake Placid Olympics.

Do the Americans and Canadians feel anything more in that game considering the makeup of the teams? Not according to Leaman.

“Canada’s two best players are college guys, Jonathan Toews and Andrew Cogliano. They have six great ‘D,’ but their top guys up front are Toews and Cogliano.”

A High Price To Pay

Rules enforcement has eliminated some of the hacking and whacking in college hockey, but trying to legislate all stickwork out of hockey is probably like hoping soft-money contributions to political campaigns go away.

However, a new issue has arisen regarding slashing and the time-honored tradition of the hack and whack. It is not injury, it is not penalties. It is breaking your one-piece composite stick in the process.

These sticks are the subject of an NCAA inquiry regarding whether to eliminate them from NCAA play. According to the 2006-2008 Ice Hockey rule book, the Rules Committee would “like to explore the elimination of one-piece composite sticks. Rationale: These type of sticks break frequently and the committee is concerned that this creates potentially dangerous situations on ice.”

Traveling through the conferences for CSTV, this topic has generated strong opinions from college coaches. There is ongoing debate on the value of composite sticks.

As one equipment manager joked recently, “They last twice as long, but cost four times as much.” Some would argue that their durability does not outlast that of wood sticks or the two-piece shaft/blade combo, and that is part of the argument to steer players away from them.

The other is financial.

“Our stick budget is obviously the biggest single component of our overall equipment budget,” said Colgate head coach Don Vaughan. “Initially we thought that the composites would be at least comparable to the wooden stick, the message being that they would last a little longer. We are finding out that is clearly not the case.”

Princeton coach Guy Gadowsky, who had the privilege of having former Flyers coach Ken Hitchcock as a volunteer assistant during the NHL lockout two seasons ago, learned more than just X’s and O’s from the former Stanley Cup winner.

“There are some NHL teams that will not allow their players to use a composite stick when they are killing a penalty because they break at the most inopportune times,” said Gadowsky. “We have seen some huge goals scored in the NHL and NCAA where the sticks of defensemen have given way in front of the net.”

There is a prevailing thought that going back to wood, or going to shafts and blades, would not only save money, but also cure that dreaded breakage problem. Even if it could be scientifically proven that one type of stick outlasts the other, the fact remains that if you break 18 composites a season or 24 woods a season, it’s cheaper to break more woods.

Could an extra $50,000, a number tossed out by many coaches spoken to for this piece, not be put to use somewhere else?

Recruiting would be the place that it would be best served. One of the things coaches say is that they only recruit in certain areas because it is not a financial reality to hit others. There are great players in those areas, but financially it doesn’t work.

Two CHA programs, which will remain nameless, would love to better recruit the Northeast and its rich talent pool, but they just can’t afford to do it. Would it help smaller schools in the ECACHL or Hockey East spend more time in the USHL or Western Canada?

“The big issue is budget,” said Miami’s Enrico Blasi, who just came off four years on the rules committee. “I know the manufacturers are not happy about looking at this or seeing this type of debate. It is an area where everyone needs to take responsibility. We can’t grow the game when everyone can’t afford to play and that is where we are getting to.”

On that note, Dartmouth coach Bob Gaudet likened some of the decisions the coaches have to make regarding equipment to that of a CFO overseeing the budget of a Fortune 500 company.

“I think if we went back to wood it would take some burden off schools financially,” said Gaudet. “We went to one particular stick company this season for financial reasons. Dartmouth men’s hockey is my business, and I have to run it that way. When you add up the costs of composite sticks for the season for 25, 26, 27 players, that really adds up because the budget wasn’t built for that.”

Gaudet is not alone in that area. It was only a few years ago that the stick budget was based on less expensive equipment, like shafts and blades or one-piece wood. The stick budgets were a fraction of what they are now.

Thinking back to my three years in the Central Hockey League with Macon as an Associate Head Coach, where the equipment budget was part of my job, the thought of buying 144 dozen composites (we bought that many woods in 1997-1998) would have put us out of business.

Where coaches have noticed the biggest difference in the stick debate is in skill development. Wooden sticks have a dulling quality about them, a little give on the blade that makes pass reception a lot easier. The composites are lively, and coaches have seen a major change in players’ ability to handle passes.

Also, shooting is an issue. While players can now shoot harder and get the puck off quicker because the sticks are lighter, accuracy is now a bigger issue than ever. Unlike the Europeans, where hand skills are ingrained at an early age, North American kids still seem to be enamored with the sounds of pucks rocketed off sticks that hit the glass. Hitting the net has never been more of a challenge.

The elite player has mastered this issue. As Gadowsky pointed out, “Steve Yzerman didn’t seem to have a problem puckhandling and shooting with a composite.” However, even an elite-level kid like Michigan’s Jack Johnson has his accuracy issues.

In a two-game series against Miami at Yost Arena earlier this season, Johnson fired five shots wide from the tops of the circles. Giving “the manchild” the benefit of the doubt that he might have been shooting once or twice to avoid hitting a defender’s shin guards, that is still too many shots off target for someone who can contribute goals or shots that produce goals.

Take this another step further. If the sticks allowed players to get shots off quicker, and they lasted longer, then why are so many point shots still getting blocked? Why are perimeter shots getting blocked? The one-timer is the hardest shot to have blocked because the puck is gone as soon as it gets to the shooter. How many college kids, especially incoming freshmen, have a good one-timer?

You don’t see many collegians with that one-time ability. With the exception of Minnesota’s power play last season — Phil Kessel, Ryan Potulny, Danny Irmen, Alex Goligoski, Chris Harrington — all of whom could one-time it, it’s rare that you see many power plays display that shot as a tactical weapon among the five players on the ice.

Minnesota Golden Gophers TV analyst and former coach Doug Woog said to me that “so many kids these days don’t develop the one-timer until they get to the NCAA because they break so many sticks practicing them, and that costs money.” That’s very true in leagues outside Tier I and Tier II Junior A, where players are still buying their own sticks in the U.S.

One father at a recent junior practice mentioned to me that he makes his kid take wood sticks to practice for shooting drills. His son, a defenseman, probably shoots between 100-200 pucks a practice and he told me he simply could not afford to have his son break a $190 stick each week in practice, let alone one a game due to the slashing and other aspects of a junior game.

OK, revisit the durability issue. If the composites were more durable, this argument would be voided somewhat. But when taking a one-timer, the amount of force coming down on the middle of the stick — its weakest point because it’s hollow and there is no support to that area — is often too much for the stick to hold up. That breaking point weakens quickly, and there goes your $190 stick.

For the chance to develop one of the best weapons in hockey, it would seem to make sense to use a cheaper wooden stick, because the return on your investment is actually greater. Break four woods and you are still in better financial shape than breaking one composite, and have probably use them way longer.

“Remember,” said Harvard head coach Ted Donato, a longtime NHL player, “those woods are almost like fiberglass composites themselves. That’s not your grandfather’s wood stick anymore. Wood sticks are lighter than they used to be.”

Speaking of “your grandfather’s wood,” or in this case their dad’s wood sticks, two of the NCAA’s elite players last season used wood, just like their Hall of Fame fathers. Denver’s Paul Stastny and Patrick Mullen have used woods since they were kids. Stastny is in the NHL now with the Avalanche and is still scoring.

Some of college hockey’s coaches have recently spent time at the NHL level where the skill level is the highest in the world. Walt Kyle, now at Northern Michigan after spending the past few seasons as an assistant with the New York Rangers, remembers a time in practice where the composite stick made a big impact on a little guy.

It is the first day these composite sticks came out and Theo Fleury got on the ice. He skated a bit, got warmed up, and started shooting pucks. He comes back over to Kyle and said “Walt, someone is going to kill someone with this thing one of these days.”

“It changed the philosophy of a shot because these guys knew they could rip the puck harder than ever,” said Kyle.

“I was winding up my career just before the composites came out. I was using a shaft and a wood blade and I thought there was a lot of upside to that. You could feel the puck better,” said Vaughan. “With the composites, the guys feel like they can shoot the puck harder. To me, it’s about control and being able to handle the hard pass. You see a lot of pucks bouncing off sticks.”

Boston University head coach Jack Parker, he of the 700-plus wins and 30-plus years of experience feels that the NCAA rules committee must be cognizant of the next level in making this type of decision. While the NCAA game is still different than the NHL game, it is closer in design than it has ever been. That has to be factored in to any decisions.

“I wouldn’t want to do anything the NHL doesn’t do,” said Parker, who has twice been offered the position of head coach of the big-league Bruins in Boston. “However, these sticks are breaking at inopportune times. With a wood stick, you know it’s about to break. You can tap it on the ice and hear it; it sounds different. A baseball bat is similar.”

Parker also sees it from the perspective of the stick companies.

“The quality of what we get from our stick company is fabulous, our guys love it,” said Parker. “I’m not trying to put the composite companies out of business when I say this, but I think it makes a lot of sense to go back to a wooden stick, to me.”

As a coach, you challenge yourself to make every player better. Your elite players have different challenges than your foot soldiers or grinders. Look at a player like former Maine Black Bear Jon Jankus. Jankus usually played a third-line role but improved every year, especially his hand skills. He was a guy who probably improved his goal totals because he knew where to be, had a quick release, and was well-coached.

That third- or fourth-liner who wants more ice time needs to do things to earn that time, and scoring would help. To score you have to be able to take a pass under pressure, corral it, and fire a shot.

“There are many third-line guys or fourth-line guys who would sit with you and tell you that they can score more goals because of the composites because they can shoot the puck harder,” said Rand Pecknold, head coach at Quinnipiac. “What happens is that they don’t handle the puck well enough in front of the net or they get a good hard pass and it bounces off their sticks. From a coaching perspective I really think it hurts some players.”

The challenge to coaches when it comes to their seventh through 12th forwards is to get a 12-goal guy to score 20, a five-goal guy to get 10, and so on. The stick usually has very little to do with it, with the exception of where the player decides to shoot. Watch some of the great goal-scorers and where they score from. The key to scoring is finding open space, and the faceoff dots in the offensive zone are usually a place where good goal-scorers go to get passes because they always seem to be open.

Watch a puck battle in the corner, and watch the dots. Open space! However, if you’re there and you can’t control the pass or hit the net, it doesn’t matter how open you are.

That is the message coaches are telling their players, some of whom do not seem to listen.

Michigan State’s Rick Comley added to that sentiment.

“I don’t think there is any reason to have it. It breaks too much, and it’s difficult to receive passes. Certainly it helps your shot. Anyone who picks it up will shoot better, but you have to be able to receive a pass to shoot the puck.”

Quinnipiac’s attempt to steer players away from the composites has nothing to do with money. Pecknold says the program is well-funded, and that players are free to use what they want.

“We had a kid who scored 18 with a shaft/wood blade combo. The next year he went to the composite and scored 10 or 11. He didn’t have as many shots on goal either. I saw that he was struggling to handle the puck in tight spots. I tried to talk him out of using the composite, but he didn’t listen and his production dropped.”

Image is everything, as displayed by the many me-first, chest-pumping, end-zone dancing or slam-dunk gyrations shown by athletes at all levels now. Hockey is no different, and the use of composites, like the use of the blue tukks used by Wayne Gretzky in his Oilers’ days, is done because that’s what the kids see at the level ahead of them.

“In the NHL, the best league in the world, not everyone uses a composite,” said Comely. “That stick isn’t the answer to everything. In college hockey, it’s a buzz thing. Kids see it in the NHL and want to use it here.”

Break it down further. In lacrosse, different positions use different length sticks. In hockey, would it make sense to choose a stick by position?

“I think a lot of our players don’t need to use the composite stick,” said Michigan’s Red Berenson. “Particularly our defensemen or players that just think it will improve their shot. But they don’t score anyway. I’m old-school but I’m also receptive to new ideas and for things that are going to be for the good of the game. The question is, are these sticks good for the game?”

Whether the stick is good for the game, or the players who play with it, is still open to debate, but what isn’t is that that stick guarantees you success. There are those with the shaft/wood blade that do well, and there who use the composite who are also successful.

However, it seems in talking to 20 or so coaches at the NCAA level, the consensus is that outside of the high-end players, like North Dakota’s T.J. Oshie, Michigan’s T.J. Hensick, Boston University’s Peter MacArthur or Harvard’s Jon Pelle, the two-piece is a better option.

“We have a picture in our dressing room of Joe Thornton from last season,” said Ohio State coach John Markell, an extremely skilled forward during his NCAA and professional career. “He led the NHL in scoring, and he uses a shaft and wood blade. Ryan Smith of Edmonton, another great player, also uses the two-piece stick. I’d rather have something that allows me to handle the puck better than get off the big bomb. I mean really, how many chances to you get to get that big shot off anyway?”

As Boston College coach Jerry York pointed out, schools started using aluminum bats to replace wood because it was cheaper and lasted much longer. However, we now see a debate on those bats, as kids are getting hurt due to the velocity of the ball coming off the bat — especially the pitchers, who are essentially defenseless.

It is the hottest topic in amateur baseball: whether to ban aluminum bats.

How this shakes out, and the financial ramifications that go with it, will play out in the next two seasons. However, should the composite be banned, it might not change the financial landscape.

As Kyle said, tongue in cheek; “If they ban the composites from NCAA play, the wood stick companies will just raise prices and it won’t make any difference.”

Hockey Is A Lifestyle For Alaska’s ‘Greener’

Kyle Greentree, the star shooter for the Alaska Nanooks hockey team, was no exception to team traditions on Nov. 15.

When his teammates lined up in two rows on the ice facing each other, Greentree, or “Greener” as he’s called, knew he was looking at an alleyway of pain. Bracing himself, Greentree flew down the stretch receiving hits in his back and legs as his teammates laughed at his misfortune knowing that sometime in the future they would share the same fate.

In the end, Greentree, laughing at his possibly bruised backside, skated off the ice with his teammates and friends celebrating what could only described as a good birthday, hockey style. Growing up in British Columbia, Greentree couldn’t help but be involved in hockey.

“That’s what you do,” he says.

Greentree strapped on his first pair of skates when he was 3. At age 6, he was playing competitive hockey, skating and shooting in the minor leagues. Greentree admits he didn’t get really serious until he was 11-years-old when, with his parents’ support, he started playing in tournaments.

From there, Greentree’s career took off. He finished first in goals and second in points in the entire Canadian Junior A Hockey League one year. When he left the Victoria Salsa’s in the British Columbia Hockey League, whom he had played with for four years, the team had his No. 39 jersey retired.

But Greentree’s favorite hockey accomplishment from his pre-UAF career had to be in junior hockey when he pulled off a “Gordy Howe” hat trick, in which he shot five goals, provided three assists and got into a fight at the end of the game.

In 2004, Greentree started playing for the Nanooks. He had hung out with Curtis Fraser, Lucas Burnett and Nathan Fornataro during his summers in Canada, and they recommended he join the team.

“It was a no brainer,” Greentree says, considering the coaching staff and Fairbanks’ reputation a great hockey town.

Since his freshman year, Greentree has consecutively held the top shooter position and was named most valuable player last season. Things are already looking great this season for Greentree. He’s been named on several occasions the Central Collegiate Hockey Association’s Player of the Week, and his pulled off his first collegiate hat trick versus the Nebraska-Omaha Mavericks in a mere 11 minute span in the first period.

Recently Greentree scored a second hat trick versus Lake Superior State ending the game 3-1. Greentree says that he couldn’t do it without his teammates.

“[They’re] all on the same page and we all get along,” he says.

Along with great teammates comes a fan base that Greentree describes as “people that aren’t your typical down in the mid-west Americans.” Instead, they’re people that know their hockey, he says.

The only downside Greentree has found playing for the ‘Nooks is the travel and long flight delays. Layovers can last four to five hours, just adding to already long flights from Lower 48 games.

After regular team practices, Greentree is often seen putting in additional time on the ice working on getting stronger on his skates and his already formidable shot.

Along with his hockey career at UAF, Greentree is majors in justice, though he admits he’s not exactly sure what he’ll do with the degree. Maybe he’ll become police officer, he says.

He’s also a big fan of cooking shows and testifies that deep down in his heart what he would truly like to do is become a chef and run own his restaurant.

For the time being though, Greentree is focused on this year’s season, hoping to get a scholarship and perhaps even a National Hockey League contract.

With a boyish grin and laid back demeanor, Greentree, always anxious to get back on the ice, leaves with a lasting comment: “This year’s team is going to make some noise in the playoffs.”

And Kyle Greentree, No. 39, will surely be the loudest one there.

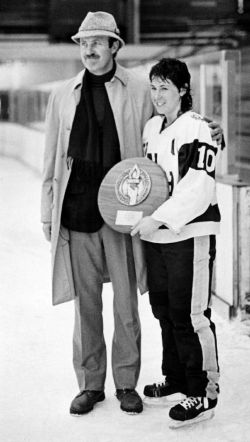

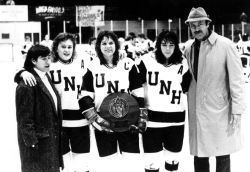

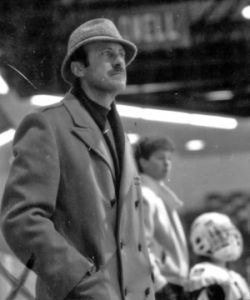

McCurdy’s Legacy Lives On

The University of New Hampshire honored a legend in women’s hockey recently when the athletic department established a gallery reflecting the achievements of former coach Russell J. McCurdy.

“He was a fantastic coach and a legend at UNH,” said former player Bridget Stearns who helped organize the Dec. 10 unveiling of the gallery before 80 former players, their families and countless others connected with the university and the program.

From 1978 to 1992, McCurdy coached the Wildcats to a 264-36-10 record (.868 win percentage) and carried them to undefeated seasons in his first four years at the helm. His teams won EAIAW championships from 1980 to 1983 and four ECAC titles in a six-year span from 1986-1991. He lay the groundwork for what is now the winningest women’s hockey program of all-time.

“He basically took decent hockey players and turned them into a machine,” said Stearns. She played from 1982 to 1986 under McCurdy, who she described as a very reserved and modest man.

McCurdy was touched upon discovering an entire wall in the school’s Whittemore Center filled with pictures, plaques and other tokens of his years as coach. The wall was also formally named “The Russell McCurdy Gallery.”

“It was very moving. I never expected anything so elaborate with gold letters on the wall,” said McCurdy, who makes his home in Lee, N.H., not far from Durham, where he coached for nearly 15 years. He was most touched by the turnout of players and their families.

“I hadn’t seen some of them in years — they all look so great with their beautiful children with them,” he said. “I started remembering things I had kind of forgotten.

When McCurdy first arrived in Durham, he wasn’t sure how it would all play out. He had been an assistant men’s coach at Yale, but he left knowing UNH was committed to building a women’s program. “I needed a change of scenery,” he said.

Women’s college hockey was still in its nascent stages back then. The players were initially all walk-ons. Many played in Sunday leagues in their hometowns. Many players were from Massachusetts, which had a strong high school and prep hockey leagues. Eventually Canadians took notice of the Wildcats’ success and began to join them.

“They were like a blank slate. I could introduce new things,” McCurdy said of his first players. Many had played during their lives but weren’t used to coaching and other aspects that go into building a contender.

At the time he took the job, the Soviets were dominating world-class hockey. “They moved the puck well and were more elusive in their play than physical,” he said, adding that this style fit the women’s game since there was no body checking.

Stearns said McCurdy was devoted to the Soviet style of hockey. “He was very strategically oriented,” Stearns said. “He studied their practices and their players, and then he taught us how to play.”

Although he introduced methods he had picked up studying the Russians (he even went to Lake Placid when they were playing the U.S. leading up to the 1980 Olympics), he was careful not to make them self-conscious about using them. “Then they would stop and think and become too studied,” instead of just going with the flow of the game, he said.

Modest to the core, McCurdy likes to think about his success at UNH as a “happy coincidence” of timing, players and skills. “I kept thinking ‘How did this happen?'” he said. But he acknowledges that he knew what to do with the talent he was given. “I’ll take credit for that,” he said. “I had some players who already excelled and they had my highest regard,” he said.

Gaby Harooules Fecteau, who played for McCurdy in his first four years, praised her former coach “as a true student of the game. His demeanor was quiet but always purposeful, and you always knew what he wanted,” she said.

She also pointed out McCurdy’s willingness to fight for things — ice time, equipment — to improve the team. He was successful in getting a skate sharpener and then sharpened the blades, himself, she recalled.

Fecteau, who played basketball her freshman year, used to sneak into the rink to see the team and check out the coach. She had played with boys most of her life. “He never knew this but I decided about halfway through my first year in basketball that I wasn’t quite ready to hang up my skates,” Fecteau said. Inspired by McCurdy’s knowledge and presence on the ice, she tried out the following year and made the team that she captained her senior year. “We never lost a game and I learned quite a bit about hockey and life being part of his teams,” she said.

Fecteau, who is vice president for the Wakefield Cos. of Danvers, Mass. and Stearns, who is a cost analyst in industry in New Hamsphire, said they were happy that the UNH administration took the time to recognize McCurdy’s contribution to the sport in a lasting, memorable way.

McCurdy’s legacy also continues in former players who have become coaches themselves. One is Erin Whitten Hamlen ’93, the goalie for McCurdy’s last two ECAC championship squads. Hamlen was an assistant on the UNH women’s coaching staff for six seasons, and she was promoted to associate head coach this past year. She has also recently served as an assistant on the U.S. national team staff.

“Coach McCurdy’s ability to be inventive in aspects of our game influences me in my coaching tendencies,” Hamlen said. “I’m willing to take more chances in my decisions on the ice. Also, his passion for the well-being of the players (as people too) really struck me as something that I wanted to carry into my coaching career.”

Katey Stone ’89 began her college coaching career in 1994 shortly after McCurdy ended his. Stone’s 13-year tenure at Harvard has included four ECAC postseason titles, four Frozen Four appearances, and a national title in 1999. With her 20th win this season, she will surpass her former mentor’s career win total.

“Coach taught me the importance of fundamentals and the little things,” Stone said. “His discipline was apparent in repetition. We were the best passing team year in and year out.”

“Coach was adamant that education came first. He was a quiet man with a fierce competitive nature. Calm, yet aggressive. I admire Coach for his dedication and passion for hockey and

education through sport.”

After retiring from coaching women’s hockey, McCurdy coached boys high school tennis for a while. He still plays tennis himself. He gets to most UNH games and thinks the No. 3 Wildcats (14-2-3) are poised to challenge at the highest levels this season.

McCurdy says he misses coaching but there are so many other things that go into a program. “It would be hard to pick it up again,” he said. So he’ll enjoy his old team and watch as they continue to excel.